" Samira Makhmalbaf "

by Nicole Mowbray

New Statesman

Monday 17th October 2005

10 people - Nicole Mowbray on a precocious director whose films speak for oppressed women everywhere.

Samira Makhmalbaf has been likened to Sofia Coppola. Both are young and attractive and both have famous film-director fathers. The similarities are obvious - but so, too, is the glaring difference. Samira was born and raised and lives in Iran, and her films reflect the tricky issue of being a woman in the Middle East today. Life for a female film-maker in Tehran is quite different from that of a woman making films in Los Angeles. Flouting the conventions of the Islamic culture in which she works, Samira reaches out to an international audience of women challenging oppression. She makes technically precise, top-quality films for which she has already gathered an international following.

Under the tutelage of her father, the legendary Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Samira made her first feature film, The Apple, at the age of 17. The Apple documented the struggle of two Iranian girls, imprisoned at home for 12 years by their impoverished parents. Produced and distributed entirely through the family-run Makhmalbaf Film House, it was a scream of protest against fundamentalist patriarchy.

When her next film, Blackboards, won a prize at the Cannes Film Festival, she dedicated her award to "the new, young generation which struggles for democracy and a better life in Iran". The media loved it; even Jean-Luc Godard paid homage.

Samira, whose particular combination of background, talent and conviction enables her to reach out to millions of women, left school at 14. "I hated school," she once said. "They tried just to give you answers, answers, answers and not let you experience or ask questions or see differently."

Now only 25, with four films under her belt and another on the way, she is a skilled and confident professional, a figurehead for Middle Eastern women, but also for women in the film industry the world over. Don't think of a preachy do-gooder, though. Samira markets herself astutely, conducting interviews in near-perfect English, her manicured nails rearranging her hijab as she speaks. She has been described as "disarmingly chic".

On set, she is ruthless, energetic, even a bully. She knows what she wants and her directing is ferocious. Her siblings made a documentary of her film-making style. It shows Samira striding around Kabul accosting strangers and insisting they act in her film. She is shockingly direct, confronting an elderly mullah with an untraditional lack of deference.

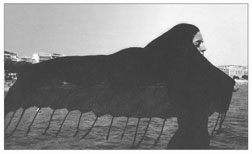

Such audacity and courage make this young director important. In At Five in the Afternoon (2003) - her fourth film - she considers Afghanistan's future, post-Taliban, and asks whether Afghan women will emerge from underneath the burqa and take power. The film begins with her asking girls at a secular school in Kabul if there will ever be an Afghan Benazir Bhutto or Indira Gandhi. As an observation about the privations of life in Afghanistan, it is profoundly moving, but it has far wider resonance. "We have our own Taliban [in Iran]," Samira said at the time, "Afghan people have their own Taliban, American people have their own Taliban." Her film explored the mechanisms and cultural norms that stifle young women the world over.

Yet, as Samira achieves international recognition, Iran's strict film censors are making it difficult for her work to be seen in her home country. Joy of Madness, the documentary about the process of casting At Five in the Afternoon, was banned when Samira's own headscarf was deemed "insufficiently modest". "I didn't try to be a symbol . . ." she has said. "But it's good. When you break the cliche, some other people come. We need one person to do something, and then it's easy."

"A brave and intelligent girl can make her own decisions," announces one of Samira's film heroines. That vision of alternative futures encapsulates her importance. Her hard-headed determination to disseminate her views guarantees that her voice will be heard for decades to come.

This article first appeared in the New Statesman. For the latest in current and cultural affairs subscribe to the New Statesman print edition.